The Takeaway: Engagement is an important process that takes time and thoughtful effort from planning teams.

Overview

A local team of North Carolina coastal professionals from different organizations collaborated to thoughtfully engage community residents and local leaders in the Scuppernong Water Management Study. The team recognized that trust, communication, and strong working relationships would be crucial to the long-term success of this study. The engagement component of the project aims to build stronger relationships among watershed residents, local governments, and regional agencies.

Lessons Learned

- Look back before you look ahead. To best understand community members and the current natural environment, learn what led to the current community perspectives and landscape. For example, the project team was aware of historical tensions between government agencies and residents. The team also recognized the region was heavily ditched, drained, and logged between 1880 and 1940 for agricultural production, leaving a landscape that makes water management challenging today. Having this insight helped the team engage more effectively with the community.

- Listen and report back. Keep the public informed about ongoing findings. This not only keeps residents up-to-date but also demonstrates that they are heard. When the community sees the information they provided in the outputs, they feel valued for their contributions.

- Learn what works locally. Understanding what motivates people to attend public meetings is crucial. The team incentivized community members to attend their public meeting by providing a free meal from a favored local eatery, raffle prize giveaways from local businesses, a kid-friendly environmental education zone, free public transportation, and ample opportunities to provide feedback. The efforts helped reduce the typical participation barriers and led to impressive attendance.

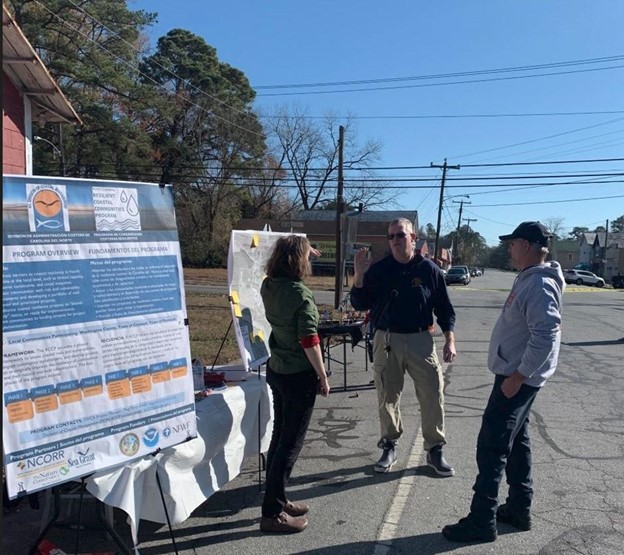

- Include technical experts in engagement. Including the engineers and technical experts in engagement activities helped build relationships and trust in the process. Sometimes, “the experts” on a project can seem like a faraway anonymous group. Their presence at community events helped build trust by allowing community members to get to know technical experts as individuals and also allowed for more nuanced dialog and direct responses to technical questions with members of the public. Having the whole study team represented demonstrated that everyone believed community voices were critical.

- Foster shared ownership of study outcomes. The steering committee for this process includes the full spectrum of agencies and organizations involved in managing water and land in the watershed. These local partners have provided substantive input and engaged in direct dialog with the engineering team at every step of the study. This collaboration builds mutual understanding among the steering committee members of the issues they all face and also helps the engineering team design the study to better address the diverse interests and needs of this group.

The Process

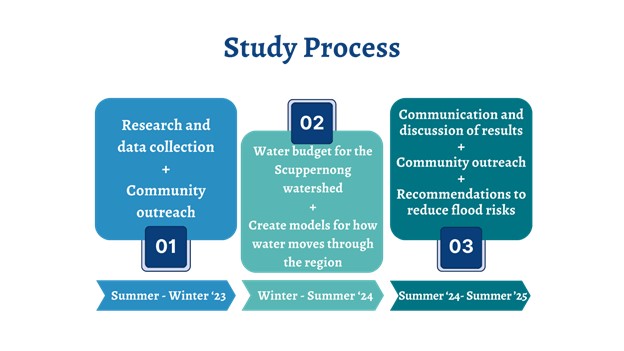

Changing precipitation patterns, land use shifts, increasing water demand, cycles of flooding and drought, and other climate change impacts intensified water management challenges in North Carolina’s Scuppernong River watershed. Because of the region’s history with wetland removal through ditching and draining to create agricultural land, once-pocosin wetlands are now miles of open farmland. As a result, this complex watershed is complicated to manage in terms of water quality, stormwater runoff, and flooding. Much of the region is conserved through public land managed by federal and state governments, and the perception exists that natural resource protection and wetland restoration efforts exacerbate flooding issues in the region.

Identifying a Need

The North Carolina Division of Parks and Recreation wanted to modernize its water management plan for Lake Phelps, which had not been updated since the 1980s. When park staff began planning an update, they realized a more comprehensive watershed approach was needed to understand and address flooding concerns. Park staff began enlisting support from surrounding organizations to start the Water Management Study. They contacted the boundary-spanning organization Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Partnership (APNEP) to serve as a neutral, science-based partner to help develop a collaborative, regional approach to watershed management. Stacey Feken, APNEP’s policy and engagement manager, facilitated an initial partnership between conservation land managers and local government partners, including the North Carolina Division of Parks and Recreation, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, North Carolina Department of Agriculture, the Albemarle Commission Regional Council of Governments (ACOG), and Washington and Tyrrell Counties. These partners collaborated on the grant application that funds the study, and funding was awarded to the ACOG in 2023. A technical contractor, Kris Bass Engineering, a member of North Carolina’s Natural and Working Lands Pocosin Wetlands team, was chosen to lead the development of the regional water management study.

Setting the Stage for Successful Engagement

Whitney Jenkins, training coordinator for the N.C. Coastal Reserve and National Estuarine Research Reserve shared NOAA’s Digital Coast funding opportunity with the North Carolina Coastal Resilience Community of Practice (CoP), which she has led since 2019. Whitney asked if there were local projects in need of community engagement funding. The Digital Coast Connects initiative focuses on supplementing or extending ongoing efforts that support under-resourced coastal communities dealing with coastal flooding. After Whitney and Stacey collaborated with CoP members, the Scuppernong Engagement Strategy project idea was developed. This funding was used to develop the Water Management Study's public engagement portion, which allowed the incorporation of local knowledge of flooding issues into the study design and improved communication and collaboration within the region through the support of the project’s steering committee.

The focus on regional interconnections and impacts also expanded the project from Washington County to portions of Tyrrell County. The watershed consists of federal, state, county, town, and private jurisdictions. Because of this cross-boundary approach and the complexities of the watershed, the engagement team convened a steering committee to help guide the study and community engagement.

-

The steering committee includes representatives from the following organizations:

- Albemarle Commission

- Albemarle Resource Conservation and Development Council

- North Carolina Coastal Reserve

- North Carolina Cooperative Extension

- North Carolina Department of Transportation

- North Carolina Division of Soil and Water Conservation

- North Carolina Forest Service

- North Carolina State Parks

- North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission

- Natural Resources Conservation Service

- Tyrrell County

- Tyrrell Soil and Water Conservation District

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

- Washington County

- Washington Soil and Water Conservation District

All of these entities have a role in managing water and land in the watershed. The steering committee plays an important role, helping to tailor the study to local needs, develop buy-in, and test messaging before engaging the public. The committee will ultimately guide local and regional decision-making regarding prioritizing and implementing study recommendations.

Whitney invited her North Carolina Coastal Reserve colleague, Woody Webster, to serve on the engagement team as a local champion. Woody has been the Emily and Richardson Preyer Buckridge Reserve site manager for over 20 years and is considered a trusted local practitioner. He could engage positively with the various partners because of his longstanding relationships within the community. Crucial Conversations, a training designed to allow successful dialogue during times when opinions differ and stakes and emotions are high, was an essential tool. The engagement team offered this training to committee members with funding from the Digital Coast Connects grant before the study even began, and the training was facilitated by the North Carolina National Estuarine Research Reserve. Engagement team members also used these training concepts in public meetings to support productive dialogue around flooding. By structuring conversations to be kind, empathetic, and focused, community members felt heard and that their time was considered important.

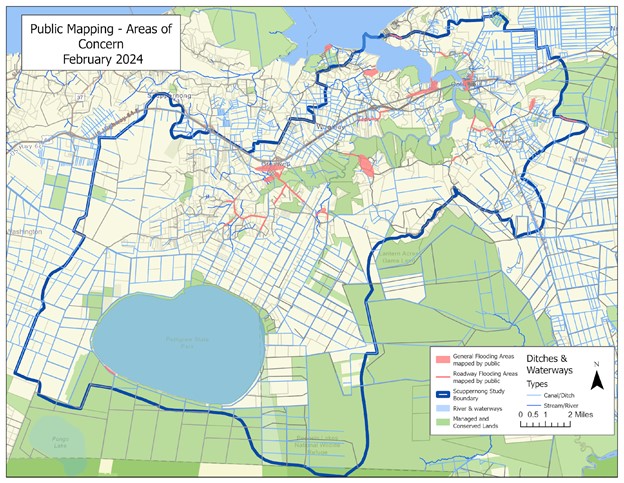

Members of the engagement team had essential roles in creating a successful engagement process. Stacey was the connection to the Water Management Study and its contractors, Whitney led the engagement process, and Woody provided historical knowledge and a local connection to the community. Cayla Cothron, a North Carolina Sea Grant coastal planning specialist, provided planning and engagement expertise. Meg Perry, a consultant with SWCA Environmental Consultants, helped develop and implement stakeholder engagement and coordinate efforts with other regional resilience work ongoing in the region, including a NOAA–funded project led by Audubon. Lora Eddy, a conservation and resilience specialist with The Nature Conservancy’s North Carolina chapter, was the participatory mapping expert and incorporated public feedback into a digital map vetted by the steering committee and shared with the water management study’s engineers. This team met regularly throughout the process to plan committee- and community-outreach activities and synthesize community feedback to guide the engineering team.

Engagement Activities

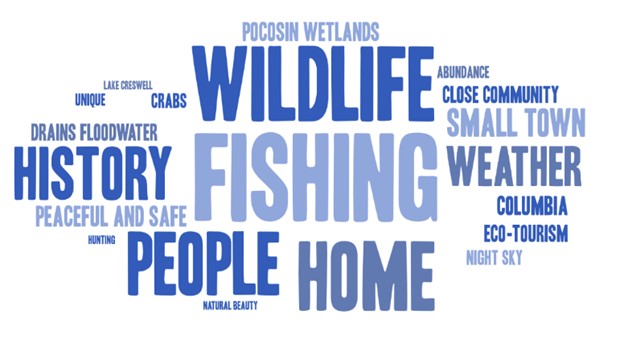

The engagement team used a variety of avenues to reach the local community. Getting out and meeting people in person at public events increased project visibility and engaged residents of all ages. The first event, a booth at the Scuppernong River Festival during the engagement phase, included a game for children and an opportunity for adults to identify areas of flooding concern on a watershed map. Visitors to the booth also discussed what they value in the watershed. The engagement team used the River Festival booth to advertise a larger community meeting later in the month. Flyers around town and posts on the social media accounts of steering-committee organizations also helped announce the event.

The community meeting focused on the study's goals, process, and timeline. Participants had the opportunity to share their stories about the region, what they value, and how flooding impacts their lives. The engagement team received positive feedback from committee members and participants about the meeting, including the ability to interact with the team at booths that focused on specific elements of the project rather than the typical presentation-style public meeting. This interactive framework allowed for more personal conversations with attendees and helped avoid having a few voices dominate the public meeting. The feedback during these events allowed the steering committee to ground-truth what they already knew about the region and identify what they might have missed.

Because this meeting was not associated with another event, the engagement team increased attendance by providing free public transportation, a children's environmental education zone to allow for parental participation, gift card raffles, and a free meal. Eating in a communal area also allowed for relationship building and continued conversations about what participants heard. These attendance incentives communicated to the public that the team wanted to share and learn from the public. Due to so much interest, a line formed to participate.

Virtual and physical copies of a community survey that mirrored the input opportunities at the in-person workshop were available at locations around the study area. The survey was intended to help capture feedback from people unable to attend the events. While there were submissions online, the response rates were low. The response rate was likely influenced by the area's rural nature, where residents may have limited access to technology or less reliable internet connectivity than other regions. Despite the few respondents, the team still felt the responses were helpful, although in the future, it might not be worth the resources (i.e., time and money) spent creating the survey.

A booth at a local Christmas parade provided another opportunity to expand the project's audience. The public could engage at two levels: stopping to talk at the booth or responding later to an online survey through a handout. The engagement team also prioritized hearing from farmers, as the community meeting took place during a busy agricultural season when many farmers could not attend. The team attended a Washington County drainage board meeting and the Blackland Farm Manager Association’s annual business meeting to reach farmers. The same information from the community meeting was shared with these audiences, and feedback was gathered from participants during each event.

Lora Eddy synthesized the local knowledge gathered from all engagement opportunities into a detailed online map of areas of flooding concern. The participatory mapping metadata included where the feedback was gathered, where the flood event occurred, and what caused the flood event. The information collected from the public aligned well across engagement opportunities, and the team felt they were aware of all significant areas of concern.

An essential aspect of these successful engagement efforts was the willingness of the engineering team, which was tasked with hydrologic and hydraulic modeling, to participate in engagement events. Their involvement established trust by showing residents that the engineering team was interested in what they had to say. Their involvement also made answering technical questions much more manageable by removing the middleman. The engineers’ participation meant answers could be provided immediately, and the engagement team was not concerned about responding incorrectly or overpromising. The team presented a range of general strategies to address findings from the modeling early, so residents would not be surprised regarding the eventual implementation efforts. This was the first experience this particular engineering team had with early public engagement, but their ability to listen well and give clear and candid responses made them successful. Directly involving the engineers in engagement helped close the loop between gathering input and integrating input into the study.

Several aspects of the engagement events made the process successful in gathering feedback while ensuring it was also enjoyable for the public. This process was cyclical, whereby the team collected information, integrated the findings, and informed the public as the project's data was updated. Historically, projects of similar scope have been extractive of resident knowledge, if considered at all. This engagement process was designed to avoid these flaws that likely led to many of the current tensions between agencies and community members. Talking with locals also resulted in a better final study, one that is comprehensive and usable. Compared to similar projects, more time was dedicated to gathering feedback, allowing for substantive relationship building. Participants also showed clear interest in hearing more about the next steps and when they could participate again. Woody Webster’s local knowledge was often handy as well, because he wa able to identify where best to hold engagement meetings. Another sign of success: Woody said he didn’t recognize all participants, suggesting that the team's outreach efforts successfully widened their audience.

Next Steps

The team is committed to continuing engagement with the community and has returned to local events, such as the Fall 2024 Scuppernong River Festival, to share updates on the study's progress. The team believes their work has been successful not only because of their thoughtful engagement strategies but also because of the quality of their working group. Each member brought their unique expertise and increased the project's capacity to keep the work moving forward. They plan on continuing their excellent working relationships as the Water Management Study enters its next phase, creating a water budget and modeling water movement through the region.

Phase two engagement will focus on communicating the study results. The engineering team will also remain involved to explain their findings through this portion of the project. These results will inform engineered designs for shovel-ready projects. The study will also assist with planning efforts for the watershed's local governments and other property owners.

Contributors

- Albemarle Commission

- Albemarle Resource Conservation and Development Council

- Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Partnership

- Kris Bass Engineering

- The Nature Conservancy

- North Carolina Coastal Reserve and National Estuarine Research Reserve

- North Carolina Forest Service

- North Carolina Sea Grant

- North Carolina Division of Soil and Water Conservation

- North Carolina Division of Parks and Recreation

- North Carolina State University Cooperative Extension

- North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission

- North Carolina Department of Transportation

- SWCA Environmental Consultants

- Tyrrell County, North Carolina

- Tyrrell Soil and Water Conservation District

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service

- Washington County Soil and Water Conservation District

- Washington County, North Carolina