Looking to the Past to Shape Future Estuaries

The Takeaway: Historical maps and elevation data reveal how 30 of the nation’s estuaries have changed over time–and where they could be in the future.

Losses and Gains: According to the study, the U.S. Pacific Coast lost much more tidal marsh than other coasts. More than 60 percent of Pacific marshes have been lost, while the Atlantic Coast saw an eight percent loss, and the extent of Gulf of America marshes actually increased.

“Restoring tidal exchange in areas that are disconnected could help restore lost habitats, but in places where wetlands are moving landward, emphasizing the protection of migration corridors may be a better approach.” - Kerstin Wasson, research coordinator at California’s Elkhorn Slough Reserve and senior author for the study

Estuaries are naturally dynamic, but human impacts coupled with sea level rise have contributed to dramatic changes over time. A recent study led by the National Estuarine Research Reserve System, NOAA’s partnership program, found that our estuaries are not only larger than previously thought, but there are regional differences in the ways they have been altered. These differences underscore the importance of tailoring conservation and restoration efforts to an estuary’s unique dynamics. New maps generated through this project can help inform those efforts, and an interactive web experience explores the past and present of all 30 estuaries studied.

“Our communities depend on the healthy natural infrastructure of estuaries to protect people and places,” said Dr. Jeff Payne, director of NOAA’s Office for Coastal Management. “Research like this provides the information managers need as they decide where to prioritize land and habitat protection, especially in light of historic investments from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.”

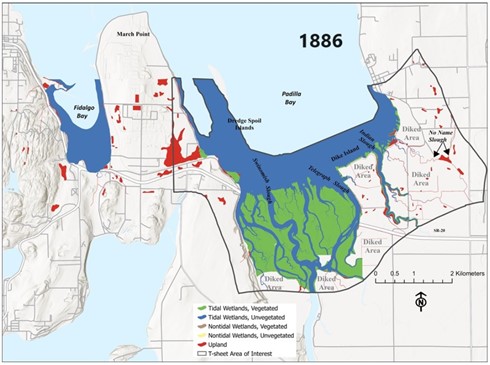

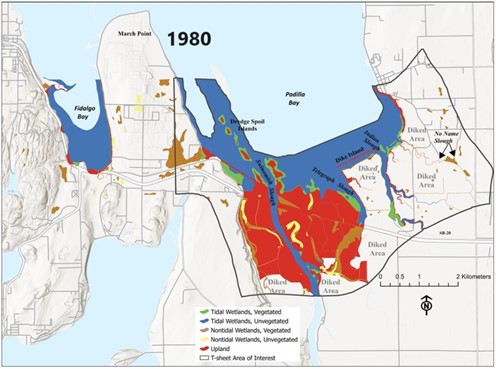

Over the three-year study, the reserve-led team synthesized land elevation and tidal data in a technique known as elevation-based mapping—a powerful way to visualize where the estuary is today, where it was in the past, and where it could be if artificial barriers to tides were removed. The team combined elevation-based mapping with historical data using topographic maps from 1846 to 1920, which helped identify areaswhere estuary habitat was lost or disconnected from tidal flows.

Comparing multiple mapping methods provides a better understanding of the true extent of estuaries—crucial information for deciding where to invest in restoration or conservation projects. Elevation-based mapping was especially effective at identifying tidal forests, highlighting these understudied tidal habitats which can be challenging to map using other methods.

The study results highlight the need for management strategies that take into account the unique ecological history of a location, rather than a one-size fits all approach. An estuary’s past can be an indication of where it could be in the future—for example, restoring a lost tidal forest can provide habitat, help store carbon, and protect the coast from storms.

While more research is needed to understand the extent of wetland habitats, this mapping effort provides powerful insights for the coastal and Great Lakes communities who depend on these estuaries.

This project was sponsored by the National Estuarine Research Reserve System’s Science Collaborative, which coordinates regular funding opportunities and supports user-driven collaborative research, assessment, and transfer activities that address critical coastal management needs identified by reserves. (2024)

Additional resources

The NERRA website provides links to detailed technical reports, GIS data, and high-resolution historical maps for this project.

Lost and found coastal wetlands: Lessons learned from mapping estuaries across the USA. Biological Conservation 299 (2024) 110779

Partners: NOAA’s Office for Coastal Management, National Estuarine Research Reserve System, National Estuarine Research Reserve System Science Collaborative, National Estuarine Research Reserve Association, Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, Institute for Applied Ecology

PRINT